A PB&J sandwich has become almost as American as apple pie, even to the point of becoming part of cultural vernacular. When two things go well together, it is like PB&J. No one talks about just a peanut butter sandwich, and very few eat jelly sandwiches. Peanut butter needs jelly, and jelly needs peanut butter. Just ask my kids.

The Alpha and Beta of investing lingo should be the same. While in some wonkish circles no one talks about one without the other, the broader investing community either denies Alpha exists or talks about it in the complete absence of Beta’s inclusion.

Three things recently got me thinking about this. Enough so that I scrapped my previous edition of the Insight that was nearly done, titled “I am Insane and the World’s Gone Crazy”. Discussing things that will have an outsized impact on our investment portfolios but that we have no control over was depressing, and further created some level of concern that some might take exception to what was being pointed out. We shouldn’t have to worry about the blow back from these things, but such is the world we live in. The three different inputs that provided a replacement topic are listed below. I will go through each one, and hopefully tie them all together with a bow at the end.

- The Warren Buffet controversy. Not quite as divisive in investing circles as Tesla; but moving that direction.

- The ongoing reappraisal of the risk/reward trade off in various segments and type of real estate investing.

- A beginning investor’s questions on debt versus equity investing.

First, we need to make sure everyone understands Alpha and Beta. Neither of those terms is normally capitalized, but since they are the star of this Insight show, I am doing so to keep our focus in the right place. Alpha, as mentioned above, is the more commonly used of the two terms, and is defined as an investment’s ability to “beat the market”. An S&P index fund, by definition, has an Alpha of zero. A stock picker’s fund (think Cathy Woods) might outperform the market one year (ARKK in 2020), and therefore have a positive Alpha. Another year that same fund might underperform the market (ARKK 2021), and therefore have a negative Alpha. The “market” is normally defined as the S&P 500, NASDAQ, the Wilshire 5000, or some other benchmark that the sponsor thinks provides the best opportunity to shine favorably on performance. With investment funds competing with each other for capital flow, it makes sense to be able to quantity returns. If a fund can’t beat the market (however it is defined), why pay them fees to invest on your behalf? But conversely, and an opinion espoused by investing titan Seth Klarman, it is ridiculous to brag about losing 12% in a year when your index loses 14%. Yes, it was a positive Alpha, but you still lost a lot of money.

Beta, as the jelly to Alpha’s peanut butter, measures the risk of an investment or group of investments. To my way of thinking, it is ridiculous to talk about Alpha without also talking about Beta. Bitcoin investors crushed S&P investors in 2020, with an approximate 800% return compared to the S&Ps 18.4% return. Quick, lets all go put all our money into bitcoin…Some people did, and some people are very sad. But seasoned investors would never do that. Sure, maybe some of the investment portfolio could/should be invested in bitcoin, but very, very few investors would go all in. Why not? Because bitcoin is viewed as substantially riskier than an S&P index fund. For a whole lot of reasons. Lack of diversification. Lack of ability to produce income as a going concern. Volatility. And many more. Does it mean that going all in on bitcoin is a bad investment? Does it mean that avoiding bitcoin all together is a good investment thesis? Like nearly everything in investing, it depends. How much risk is associated with bitcoin versus an S&P index fund? That measurement is Beta. Do the expected returns from a speculation in bitcoin produce enough Alpha to offset the increased Beta? That is really the question. It isn’t whether or not one investment outperforms the other, but rather does one investment outperform another enough based on the different risk levels (Beta) associated with each investment.

Unfortunately, there is an inherent weakness in Beta, in that the way Beta is measured is tied to volatility. But volatility is only a small component of risk. And often isn’t a measure of risk at all.

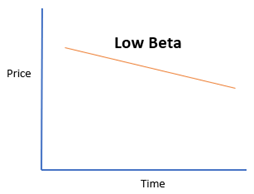

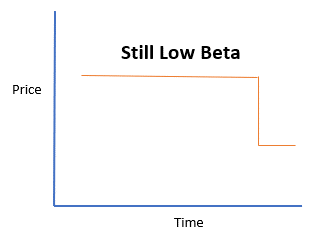

The first chart shows a stock/investment that is continually losing value, but because it is consistent in its price change it has low Beta. The second chart has high value; but had a 27% increase in stock price over the past 6 months. This is Apple. Apple could be argued to be riskier than whatever the above chart represents, but obviously a better investment (Alpha vs. Beta). But check out the chart below. This stock also has low volatility, but obviously had serious catastrophic risk, meaning is far riskier than Apple as shown above. A stock chart like this does happen, such as when an exchange halts trading on a particular security for some reason and then later opens it back up.

However, while imperfect, Beta is all we have in the financials markets. In the non-financial markets (non-bond debt, real estate, private equity, etc.), we unfortunately don’t have any proven way to measure risk at all, which makes comparison between opportunities much more difficult without a deeper understanding of the specific market and investment.

Back to Buffet. Our Board Chair and I have running debates over a variety of different investing topics. Not only is it fun for us investing nerds, it also helps us think critically about our theses (I feel pretty good about my Amazon analysis). Our discussion about Buffett is still ongoing. Our Board Chair tends to take the view that Buffett has lost his touch. I fall into the camp that we can’t yet make that determination based on a particular period of time (when there has been tons of governmental interference in the market), when that period of time is a blip on the longer investing timeline. A simple google search can turn up article after article discussing Berkshire Hathaway’s performance over the decades, with the most obvious focus being on their underperformance to the S&P over the past 15 years. Dave Portnoy, without a trace of humor intended tweeted in June 2020, “I’m sure Warren Buffett is a great guy, but when it comes to stocks he’s washed up. I’m the captain now.” Portnoy’s entire investing career fits inside just one 15-year period, and even then, Barstool Sports is a blog, not an investment entity. It is easy to brag about a good year or two when taking big positions in bitcoin (as an example), while having a short investing career and no transparency into actual investments made, or the return on those investments.

When looking through this Buffett controversy more broadly, there are two things I noticed:

- Very few to almost no articles that mention Buffett’s demise reference Buffett’s Beta compared to the underlying comparison set (S&P). Our chair sent me one just this morning. Over 25 years (thus including a portion of the previous 15-year period of strong returns), Berkshire (BRK) has returned investors 9.38% annually (compounded) while the S&P has returned 9.88%, or a relative 3.5% under performance by Berkshire Hathaway. Beta however, measures as 12.6% higher for the S&P than for Berkshire, implying that on a risk return basis BRK outperformed the S&P. But…1. This performance is supported by years outside the most recent 15-year period for which BRK is most hammered. And, 2. BRK holds fixed income instruments where as the S&P obviously does not. This lowers the Beta, but almost always also lowers the absolute returns because lower returns follow the lower risk profile of fixed income investments versus equity. Add it all up and what does it mean? I think the discussion of BRK’s performance versus the S&P is far more nuanced than the twitter and the financial press admit/realize (regardless of which side they are taking in the argument).

- A larger question to me is whether such a discussion is ever warranted. Especially when the comparison is made between BRK versus other investment funds. BRK is not an investment fund. It is an investment corporation. The investment funds hold publicly traded stock, which in turn are priced daily which makes it simple to price returns of the fund. The returns of the fund are NOT based on the stock price of the fund. Conversely, in addition to its publicly traded stock portfolio, BRK has consider private holdings, mostly operating companies. To the best of my knowledge, these companies do not have a listed stock price, so the strength of those investments does not flow straight to BRK’s performance on an apples-to-apples basis versus whichever investment fund is being used for comparison. Further, because BRK is a listed corporation and not a fund, the comparison fund’s performance is being compared to the BRK stock price movements, NOT the return of the BRK investment portfolio. It isn’t apples to apples. The same holds true with a comparison to the S&P. BRK is considered a value stock, not a growth stock. Value stocks have been penalized relative to growth (tech) stocks over the past several years. Regardless of the underlying performance within the BRK company, shrinking (or underperforming) PEs are out of the control of the company. Assuming the current rotation to value (BRK is doing quite well this year so far) continues, there will be a relative change in valuations between value and growth stocks. Suddenly BRK will be outperforming the S&P and the funds it is compared to, EVEN IF THE UNDERLYING PERFORMANCE DOESN’T CHANGE. I have no idea if Buffet has lost his touch or not. But those that are claiming he has with certainty are using faulty analysis.

The second thing that got me thinking about Alpha and Beta is Altus’s ongoing internal discussions about our own investment efforts. I wrote about it here, so I don’t need to go into detail again, but this discussion and ruminations about where the pockets of (relative) opportunity exist never stops. Yields are insanely expensive right now, and only getting more so as interest rates increase. That doesn’t mean we don’t like cash flow producing investments. They are still our favorite. And it doesn’t mean we aren’t still searching for them, because we are turning over rocks like crazy. It isn’t even that they are difficult to find. It is that they are difficult to find at returns strong enough to justify the risk. Regardless of what kind of investment you are making, even into government bonds, there is risk. When money is being borrowed, as it often is with real estate, the slimmer the net cash flow margin (measured as debt service coverage ratio), the higher the risk that investment runs into cash flow issues due to a change in operations. Therefore, the lower the total yields, in broad strokes, the higher the risk of obtaining each unit of yield. That isn’t to say the risk is out of line, nor is it to say the returns received aren’t worth taking on that increased risk. It is just an awareness of how the dynamics within the real estate investment world have changed. To tie it back to the language of the financial markets, if yields are Alpha and risk is Beta, Alpha has decreased, and Beta has increased. Again, that doesn’t mean anything in a vacuum. It only brings awareness to a displacement in the historically normal market wide return structure. For many reasons I don’t feel like we are back in a 2006/2007 situation again, but the last time we had this kind of Alpha/Beta shift within the real estate markets (especially as it relates to yield), was in the last couple years leading up to the Great Recession.

And lastly, how does debt play into this? An Altus employee, and a fairly recent college grad, is studiously applying time to learn about investing. Yesterday he asked me why people don’t invest more in debt versus equity once the risk between the two is taken into account. A great question, and not a normal mindset for someone in their early twenties. It is hard to capture this in an Alpha/Beta discussion because what is the underlying comparative index that we can use to measure debt returns versus real estate investment returns? All the same, there is no question that a generic real estate equity investment has a higher Beta than generic real estate debt, by definition of where each fits into the capital stack. And also, by the same definition, generic real estate equity should be considered to have Alpha versus generic real estate debt. So, where does the best investment lie? Like so many things in investing, it depends. For one, traditional real estate debt has very low returns, or said another way, real estate equity has considerable Alpha versus that sort of debt. If there are financial goals to be reached, it well could be that those goals are reachable via equity but not reachable via debt. Basically, the same reason people invest in stocks versus bonds. Private debt has considerably higher returns, so the alpha between real estate equity and private debt is much smaller than traditional debt. Some would argue private debt also comes with considerably higher Beta (risk) than traditional debt. As an insider into this business, I personally disagree with that statement for a number of reasons, but there are valid arguments to consider contrary to my opinion. To me the biggest issue is the availability of private debt versus equity. The private debt markets are huge, but they are tiny compared to traditional debt markets, or even the real estate equity markets. They are also highly fragmented, so opportunity goes to those in the know, or at least those that know those in the know.

This takes us back to the Buffet discussion again. It is much easier to create Alpha investing small amounts of money in niche opportunities than it is investing huge amounts of money wherever it can be invested. Before Buffett created massive amounts of cash flow that needed to be reinvested on a consistent basis, BRK was able to find those niche opportunities. The sheer volume of cash needing to be invested means they can’t spend time analyzing a promising $20 Mil acquisition. They have to invest $200 M at a time (I am making these numbers up). There are far fewer great opportunities at larger scale, so finding outperformance is more difficult. Alpha can be created, AND Beta can be reduced, by specific niche knowledge.

I am not sure how to summarize all this succinctly. I know that when it comes to PB&J, as a kid I always preferred a fresh sandwich as opposed to something that sat in my backpack through the first half of the day. As an investor I like shiny returns as much as the next person. But more than shiny returns, I like high value returns. If that means I have negative Alpha in my own portfolio versus the S&P over a course of time I am okay with that so long as I judge/measure the implied Beta of my portfolio to be enough lower than the Beta of the S&P (or whatever it is I am judging against) to determine that my risk adjusted returns are better than that of said index.

Is 8% a good return? All together now, “It depends”.

Happy investing!