I have been asked to present to a group of elected officials in Northern California in a couple weeks to discuss how financing and investment in new projects works, and by extension, how the decisions they are making as elected officials directly impact the development (or lack thereof) of new projects. Also included in the presentation will be the cost to the end users of those projects. I am struggling with the difficulty of boiling down decades of real estate and finance experience, profitable and non-profitable, into a half hour presentation. Humor me while I use this insight to try and gather my thoughts, specifically to answer the question – what are the key impacts to end pricing?

Most anyone within the industry would agree that any increase to regulation has a corresponding increase to cost. Some of this is obvious. Two nails cost more than one nail, and two nails cost more to pound than one nail. But it is the carryon effects that aren’t as obvious. Because of the increased cost in materials and labor of the two nails versus one nail, the labor driving that nail needs to earn more to be able to live close enough to the project site to pound the nails. That increase in labor in turn increases the cost of the labor beyond just the cost of doubling the labor time input, which then increases the cost of housing, which in turn increases the cost of the labor input, etc.

Much harder to be able to clearly articulate are how governmental involvement impacts the cost of financing, equity investments, and entrepreneurial profit. For simplicity in this article, we will call those items the “capital stack”. In addition to the items listed, there are sometimes government incentives or tax benefits associated with a new project. We will not address those items in this article and will ignore the broader economic/philosophical question as to whether such incentives do more harm or good to the greater economy and the participants in said economy.

A few inputs in the capital stack that need clarification before getting into the heart of the message include:

Financing: Debt can come in many different forms, but at the end of the day it has one key component. Finance providers look to limit/minimize/eliminate risk of loss and are willing to cap their return on investment as a tradeoff for the security that normally comes with being a lender.

Equity Investment: There are two basic kinds of capital used for investment. Third party investment (which can take on any number of forms) and direct sponsor investment. Often, and especially on larger projects, third party investment is highly sophisticated and detailed in their analysis of risk versus the quantifiably expected returns. Sponsor investment is usually more discretionary and able to take unquantifiable risks (otherwise known as uncertainty). In exchange for this flexibility and risk/uncertainty, the returns available to this part of equity investment should ultimately (and in general across a lifetime of projects) be much higher than the other debt/slices of the stack.

Entrepreneurial Profit: People looking in from the outside often believe that real estate investing and development is easy to do, with fat profits for all. How often do we see people make a large amount of money in one area and decide they want to become real estate investors/developers? Real estate projects result in losses far more often than anyone likes to admit, especially in the short run. Experience and skill set matter. On top of skillset is the time investment required for a successful project (clock time). As with the nail example used earlier, two hours of labor input costs more than one hour of labor input. Additionally, since most of the real estate entrepreneur’s profit comes only upon completion of a successful project, calendar time plays a role as well. The more calendar time it takes to get from start to finish, the higher the return on investment (deferred compensation) to be expected.

All three inputs into the capital stack are impacted by the ease or difficulty (and as importantly, the projected ease or difficulty) in making a project successful.

To go the next step in the logic, there are certain assumptions that need to be agreed upon. These items may be intuitive and obvious to many of you reading this, but many in the broader society that don’t take as active an interest in investing, it is not the case:

- Risk is the possibility that things don’t work out as planned. There is risk to profit (the profit is lower than anticipated), there is risk to capital (the investment isn’t recaptured), and risk to timing (distributions aren’t received when expected). All these things impact the return on investment of a real estate investment (usually measured by IRR). Risk is quantifiable. If interest rates drop by x% the cash flow increases by y%. If lumber increases by x dollars per board foot the profitability drops by y.

- Uncertainty is the possibility of things occurring that are outside the realm of quantification. A virus that shuts down a country (or the world) for a year is an example. Even if someone somewhere did include a COVID like event in their risk analysis, there is no way they could have accurately modeled the impact on particular areas of the economy or investment sectors. Uncertainty, even though unquantifiable, has the largest impact on expected investment returns. In real estate terms, most uncertainty lies up until the time entitlements are obtained. Entitlements are the discretionary approvals to develop, build, improve, or change the use of a property. Once entitlements are in hand, additional requirements are non-discretionary and uncertainty is greatly reduced.

- Investors expect higher returns, both in percentage and absolute, for longer investments. The yield curve is the most obvious example of that. Ten-year treasuries are 75 Times higher than T-bills (yes, you read that correctly) – DESPITE having basically the same market liquidity. This term premium is far more pronounced for investments with reduced liquidity. The reasons for the increased return expectations are pretty straight forward. For one, things change. Malls become obsolete, manufacturing moves to on shoring, etc. Things changing reduces the certainty/likelihood of future returns. Not only do things change, but things happen. The person signing a lease on behalf of a tenant quits and the new person on the job has different ideas. A delay in permit issuance results in steel costs spiking because the President initiates a trade war.

- Higher labor inputs equal higher expected compensation. The more real estate entrepreneurs have to work on a project, the more they expect to make from that project.

- Return calculations (and deferred compensation expectations) are based on Einstein’s greatest wonder of the world… compounding. A 20% IRR (compounded return) over 5 years with no distributions equates to total returns of 150%, while a 20% annual distributed return over those same 5 years (which would also be a 20% IRR) is 100%. To get exactly the same IRR, the first example requires a 50% increase in absolute returns versus the second, simply because it is deferred. For compensation, anyone who is willing to bypass on a dollar of compensation today wants more (and usually considerably more) than that dollar for the same labor input when they are paid in the future.

- It needs to be highlighted that when it comes to the deferral of compensation, not only is there the impact of the compounding of the deferral on the expected end compensation, but risk also plays a part of the expected end compensation. It is one thing to defer compensation with 100% certainty that the compensation will be paid in full at the agreed upon point in the future. It is another thing to defer the compensation with confidence it will be paid, but no certainty as to when. And it is yet a completely different thing altogether when that deferred compensation has less than a high probability of occurring (and as a real estate entrepreneur, that probability is often not high at all).

So, if we add up all the above mentioned considerations, we come to the following conclusions:

- The longer a project takes, the higher the costs.

- Every day comes with an associated cost of money. In absolute, year #2 of a project doubles the cost of money from year one.

- Because time also comes with higher expected percentage returns, the applied return expectations increase with time. Not only is year #2 doubling the cost of money versus year #1, but the incremental cost of money also increases. This results in a project expecting to take two-years having more than double the cost of money than a project expecting to take one year.

- This increase in the cost of money in turn increases the cost of the financing input, the cost of the investment input, and the cost of the entrepreneur input.

- Complexity increases the cost of a project.

- The more complex a project, the higher level of skill required for the project (architects/political consultants/engineers/entrepreneur/etc.). Higher skill levels are compensated better than lower skill levels.

- The more complex a project, the higher the amount of effort required in clock time. Two hours of labor input costs twice as much as one hour of labor input.

- Costs increase very quickly when higher skill input requirements are combined with higher unit labor inputs.

- Because additional funds are required to pay for these added costs, and those funds in turn need to earn a return, an increase in complexity also increases the financing/investment costs of a project.

- Risk and Uncertainty.

- In theory, risk is quantifiable so it can be modelled. The higher the probability of a negative event occurring (like a spike in steel costs) the greater the return expectations of the invested capital, or possibly the inclusion of a larger contingency or hedge. Either way, there is an increased cost to a project.

- Nothing impacts expected project returns as much as uncertainty. Nothing.

- There are certain types of uncertainty that simply can’t be planned for, regardless of where an investment is located. That is inherent in investing and can be accepted.

- Uncertainty around governmental impacts is usually attempted to be offset by increased expected profit margins. This results in underwriting that is more difficult to make work, resulting in fewer projects starting, and therefore fewer projects getting across the finish line. A reduction in finished product means higher end user costs/pricing (supply and demand).

- Governmental uncertainty increases the likelihood of unrecoverable expenses (otherwise known as losses). In areas of high government involvement there are lots and lots of these losses. Depending on where things blow up in the process, the losses could be as little as tens of thousands of dollars in costs during due diligence, or as much as millions of dollars in lost soft cost investment or loss of value. For a real estate entrepreneur to be successful, these losses have to be made up on the successful projects. A reduction in such losses reduces the required profit margins on all projects.

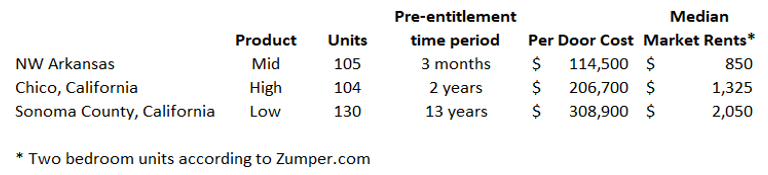

An illustration might be the easiest way to simplify this. Altus has recent involvement in multifamily projects in the North Bay (where the elected officials are to whom I will be presenting), Chico California (small non-coastal city), and the greater NW Arkansas metro. There are some differences in product type so comparisons aren’t exact, but certainly close enough for this example. The North Bay project is a two-story, affordable by design multi-family property with no amenities and a one car garage for every two units. The Chico project is a two-story Class A apartment complex with a pool, clubhouse, pet park, and much nicer finishes than either of the two other projects, but with no garages. The NW Arkansas property is comprised of single-story duplexes, each with their own backyard and garages, and with finishes between the North Bay and NW Arkansas project. NW Arkansas is the easiest to deal with (least uncertainty). The North Bay is by far the most difficult, with Chico somewhere in between.

I am writing this article on the plane ride back from meetings in the Kansas City metro, a market we really like. We have been contacted to come into the multifamily portion of a large master planned project to help the local developer figure out their deal structure and their capital stack. The cost of the capital stack, and the resulting total project cost, is the very topic at hand. Putting into practice the lessons of this article, the meetings we had over the past two days focused on a few key items:

- While we knew that construction docs have not yet been started, are there any discretionary approvals left remaining? Is there anything governmental remaining that could impact the project? How friendly is the local government to this particular project? For us it was key to understand what sort of governmental uncertainty (if any) still existed.

- What is the end user demand in the area and how fickle is that demand (According to studies done by the municipality there is a considerable shortage of for rent units)? Resident demand is a risk that can be tested/modeled for sensitivity with probabilities, then assigned to various rent level changes. This provides an understanding of revenue.

- How confident is the local developer and contractor in their cost projections, and along these lines, what has their experience been in producing projects on target with their projections (5 – 10% margin for adjustment once construction documents are produced)? Like revenue, this is a risk that can be quantified and modeled.

The meetings went very well, and based on the findings to the three questions above, we are excited/hopeful we will be able to put together a structure that works for us to become involved.

There are some that would argue that it isn’t the inputs that impact cost, but rather whatever pricing the market will bear. I actually agree with that sentiment, but costs still provide a floor on what is possible. For instance, if Apple could sell the I-phone for $100 and maintain their unit profitability, they would sell millions more units. Likewise, as in the NW Arkansas example above, because housing can be built so much more affordably than in areas with higher level of governmental restrictions, people in turn enjoy much lower housing costs, despite a population that is growing over three times as fast as the rest of the country.

The short of it is that the decisions made by local (and state and federal) elections do matter. Each decision made that impacts time or uncertainty of a project directly impacts the financial status of each person living in that community. And each decision in turn impacts the inputs to future projects, both in terms of the hard costs and the capital stack. It is really encouraging that so many elected officials are wanting to learn about the impacts of their decisions on housing. I hope that I can provide information in such a way that will be useful, and if I am successful in such, that they will take the lessons to heart.