This month’s Insight jumps around. A lot. But stick with me. With some luck it will all come together by the end.

Not including any measures by the Federal Reserve…

- March 27, 2020 – $2.2 Trillion in stimulus (CARES Act)

- December 27, 2020 – $900 Billion in stimulus (COVID-19 Economic Relief Bill)

- March 11, 2021 – $2.1 Trillion in stimulus (American Rescue Plan Act)

- Coming Soon – $1 Trillion Infrastructure Bill

For Perspective – A jet going the speed of sound and trailing dollar bills behind it nose to tail would have to fly without stop for 14 years to trail $1 Trillion, a distance of which is nearly from Earth to the Sun.

I am not particularly fond of accounting but there are certain aspects to it in which I have great respect. Most importantly, everything has to balance. Accounting isn’t theory, it is identities. It is either done correctly, and everything ties out and balances, or it isn’t, and it doesn’t. It is pretty cut and dry.

Built on the foundation of accounting comes a much more exciting discipline (at least to me) – Finance. Even as accounting reports what has happened, Finance is looking forward to what will, or might, happen. But it still requires the same foundation of everything tying out and balancing.

Both Finance and Accounting would consider $6.2 Trillion a massive amount of money. An unfathomably large amount of money. The question is whether it was (or will be) well spent or not. With the caveat that I am fiscally conservative, lets discuss.

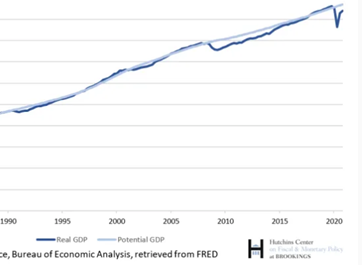

In 2019 the US economy, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), was $21.43 Trillion, an increase (including inflation) of 4.1% from 2018. While not perfect, it is a reasonable proxy to assume that sans the coronavirus impacts 2020 GDP would have grown a similar amount, resulting in approximately $22.3 Trillion in 2021 GDP. This is a theoretical number, but with years of trends to analyze most people would agree that it is a relatively accurate projection. This is what we will use as our baseline for 2020 economic projections. This could also be called, “potential GDP”.

COVID-19 responses (whether through personal choices or governmental restrictions) resulted in severe economic losses. In the chart below the light blue line shows the GDP trend line while the dark blue line shows actual GDP. The difference of the dark blue line above or below the light blue line is called the output gap. The economic crash that occurred last year is easy to see.

There are a couple key points to keep in mind:

- Spending (stimulus) can be funded by only two things: revenue or debt

- Debt has to be paid back or defaulted on

- For debt to be paid back, revenues have to be enough greater than expenses (over time) to pay the debt principal. For a business this is called a profit. For a non-profit, like a government, this is called a surplus.

- To create a surplus, especially for a government already running a heavy deficit, either taxes have to be increased or expenses have to be reduced. Governments are not good at reducing expenses until the bond market forces them too.

- The vast majority of the higher taxes will be paid by generations other than the current taxpayers. This is namely our kids and grandkids and in turn their kids (and likely their kids’ kids and their kids’ kids’ kids).

- The stimulus was a benefit to current and past taxpayers but will be paid by future generations.

- If the government defaults on the debt instead of paying there is obviously a substantial direct impact to the lenders (bond holders), but there is also an intense impact across the broader economy and society. Recent years’ events in Greece and Argentina have shown this to be true.

- Many of the economic losses, especially among small businesses, were caused by the government reaction to the virus.

The reasoning (or justification depending on your point of view) for the stimulus packages and the upcoming infrastructure package was to offset the losses tied to the COVID-19 impacts. Disagree or agree with the wisdom of debt funded stimulus (as described above), one has to acknowledge the reasoning behind using stimulus to offset the economic losses. This is not unlike what a company might do in pulling money from their line of credit to cover payroll during a high expense or low revenue period. And, unlike companies that might make such a move without knowing if they can survive (and therefore putting the repayment of the debt in danger), the government knows it can survive because it has the power to raise taxes. Unlike a company who may lose customers because of higher prices, governments, especially on the federal level, have revenue increasing powers that are close to absolute.

So, if there is some level of logic in the stimulus at large, what about the amount of stimulus? As discussed above, there has been $5.2 Trillion in stimulus not including the upcoming infrastructure bill. Determining if was the right amount then becomes an easy math problem. The chart above measures the output gap, which based on calculations was roughly $1.6 Trillion. Some would argue that it could be considerably larger, and since our economic potential estimate is just that, they might be right. So, let’s double the assumed gap to $3.2 Trillion.

Through the second stimulus bill the stimulus total was $3.1 Trillion, or pretty darn close to our (higher) output gap. The third stimulus was, therefore, not a replacement of lost economic activity, but rather debt fuel spending to magnify growth beyond the natural trend line.

There are issues with this. When the economy doesn’t have the capacity to handle the “investment” (labor and material shortages already exist before more demand is introduced into the system) the stimulus doesn’t fuel growth as intended, but instead it fuels inflation.

None of the above takes in account the impact of the additional inflationary boost of the infrastructure bill.

My analysis, and therefore my opinion, on the matter may surprise you.

- I don’t know what to think about the stimulus in general. I am normally pretty skeptical about government spending from a position of deficit. Very rarely would/could anyone run a private enterprise in such a manner. But at the same time, it is impossible to see the damage done by the coronavirus response, so if there was a time to borrow and spend, this was certainly it.

- However, I think it was extraordinarily irresponsible to pass the stimulus bill this spring. Previous stimulus had already provided for what was lost (and arguably more), therefore this stimulus was purely fuel on the fire. Granted, people love getting checks in the mail so of course the population at large would be in favor of the additional stimulus, but very few employees in a company would say anything other than everyone should get raises – who cares about the long-term viability of the company. Appropriating the wealth of future generations to get votes today is insultingly short-minded.

- Then there is the coming infrastructure bill. With inflation already red hot (at least in the short term) and shortages of labor and materials everywhere we look, another $2 Trillion investment into the economy will only exacerbate the extremes that already exist.

This is where my opinion might surprise you. Going back to accounting being the foundation for finance and economics, there are two documents that are the starting point; the income statement and balance sheet. Everyone reading this Insight knows that an income statement measures what you make, and a balance sheet measures what you have. Many people would also say that an income statement also measures what you spend, but that is not technically true.

Politicians and economist will never boil it down to simple terms, but at the end of the day, government accounting is essentially the same as a private sector income statement. There is revenue (taxes), and there are expenses (military, social programs, interest expense). Subtract the second from the first and you have profit or loss, or in the governments case, deficits (common) or surpluses (very uncommon). The balance sheet is where you find considerable divergence between government and the private sector. In Altus’s business we spend millions of dollars per year that doesn’t touch the income statement. Whether it is renovating apartment complexes, doing ground up construction, or upgrading our accounting software, all these costs are not expenses, they are investment. As such they are recorded on the balance sheet and not the income statement. That investment, if done correctly, should result in future revenue, resulting in (all else being equal) an increase in profit.

The government doesn’t differentiate its spending between investment and expenses. This is absurd because there are good uses of money and bad uses of money. If I can borrow money at 3% it makes sense to invest that money in something creating a 10% return. There is a benefit to me as the borrower and investor, and a benefit to the lender in that they have a broader base of income and wealth from which to be paid back. If instead I take that same money and spend it on drugs and rock and roll, I wake up the next day with nothing but a headache, some hazy memories and more unproductive debt hanging over my head. The same holds true for government spending. There are things the government spends money on, many of them even necessary, that benefit the long-term economic prospects of the country. Others have a distinct and documentable return on spending.

This ties back to the infrastructure bill as such:

- It is impossible to think about government spending and not acknowledge that the government is about the least efficient allocator of spender possible. The waste, red tape, and bureaucracy is insane.

- The country’s transportation, power grids, water storage, and internet access (and more) are crumbling. This hurts our international competitiveness, contributes to climate change, and often has an outsized negative impact on the youth from low-income families.

- If viewed from the perspective as money spent on infrastructure being an investment in the future, which if done correctly it certainly is, then the economic returns through increased tax revenue (via increased incomes, not increased tax rates) created by the investment far outweigh the cost of borrowing the funds for said investment (especially at today’s low rates).

- As such, I am fully behind a plan to invest in the country’s infrastructure. In a perfect world this sort of investment would come during times of economic slowdown (2009 and 2020) and not during times of red-hot growth and burgeoning inflation, and the money would be spent efficiently/effectively on projects that can be documented to provide certain minimum economic returns (versus more pork barrel allocations). Today is not a time of economic slowdown and I have little hope that the government will ever be able to allocate funds in an effective manner, so with that realization I am okay settling for pretty good, and not holding out for perfect. And thus, and despite my frustration with the last stimulus bill, I am in full support of an infrastructure program.

From an investor’s perspective, having inflation rates higher than interest rates makes for some interesting (almost arbitrage) opportunities. Additionally, even if none of the favored groups (per pre-existing government definitions) directly receive a portion of the infrastructure spending, sharp eyed investors will still be able to take advantage of the infrastructure upgrades through tangential opportunities.

Happy Investing.